Fifty years after the world’s first deep-sea mining test off the US East Coast, the Blake Plateau remains visibly scarred. Though the original pilot was small in scale, the damage remains etched into the ocean floor — and with new efforts to fast-track industrial-scale deep-sea mining, scientists are sounding the alarm once again.

A Wound That Never Healed

In 1970, US company Deepsea Ventures conducted a groundbreaking test on the Blake Plateau off North Carolina, vacuuming up 60,000 manganese-rich nodules from the ocean floor. These nodules — containing cobalt, nickel, and other critical minerals — formed slowly over millions of years. The experiment was short-lived and the project was abandoned, but the impact was long-lasting. In 2022, a scientific expedition rediscovered the site and found dredge lines stretching more than 43km (27 miles). These deep furrows in the mud remain lifeless and barren, in stark contrast to the teeming marine ecosystems nearby.

Microbiologist Samantha Joye, who visited the region in 2018, described the untouched areas as vibrant and diverse — full of mussels the size of forearms, octopuses, sponges, and bioluminescent sea life. But just beyond these rich zones lie wastelands where biodiversity has yet to return even after five decades.

Fast-Tracking a Controversial Industry

Despite those clear warnings from the past, the US is now racing toward large-scale deep-sea mining. In April 2025, President Donald Trump signed an executive order titled Unleashing America’s Offshore Critical Minerals and Resources, aiming to expedite permits and approvals. This includes efforts by companies like The Metals Company and Impossible Metals, which claim their mining technology is far more sustainable than past methods. The latter even proposes picking nodules one by one without disrupting the seabed.

Still, scientists remain skeptical. “All mining has impacts,” said Impossible Metals CEO Oliver Gunasekara, while advocating for environmental impact assessments. However, the vast unknowns of deep-sea ecosystems — 70% of which remain unmapped — pose major challenges for meaningful assessments.

Lessons from the Clarion-Clipperton Zone

The Pacific’s Clarion-Clipperton Zone, located southeast of Hawaii, has become a flashpoint in the global debate. Mining simulations conducted there in 1989 showed that microbial and animal life still hadn’t fully recovered 26 years later. A 2025 study confirmed that ecosystem resilience may span centuries, not decades — and that’s under controlled conditions. Larger-scale commercial activity could leave permanent damage.

This zone holds immense resource potential — reportedly containing more cobalt, nickel, and manganese than all land deposits combined. Yet studies show that 90% of its species are new to science. Losing these ecosystems before we fully understand them could mean missing out on future breakthroughs in medicine, carbon storage, and biodiversity conservation.

Risks Beyond the Seafloor

Beyond the seabed itself, scientists worry about sediment plumes released during mining — underwater clouds of particles that can travel long distances, disrupting ecosystems far beyond the mining zone. These plumes may affect jellyfish behavior, fish feeding patterns, and communication through bioluminescence. They also risk interfering with the deep-sea carbon cycle, which draws down up to 14% of human-generated carbon emissions annually.

“It’s unclear what this means for climate regulation,” says Christopher Robbins of Ocean Conservancy. “But the risk is real.”

Robbins’ recent report also warns of conflict with fishing industries, especially tuna fishing in the Pacific, where migratory routes overlap with potential mining zones. Some small island nations could see up to 10% of their tuna catch affected by such activity.

The Blake Plateau: A Cautionary Tale

Although the Blake Plateau is not currently targeted for commercial mining, its role as a case study is crucial. In 2024, scientists discovered the world’s largest known deep-sea coral reef there — spanning 500km and containing more than 83,000 coral mounds. Fish ecologist Gorka Sancho has called for lasting protections, noting that previous bans could be reversed by political shifts. “Everything can change on a dime these days,” he says.

Regulation in Question

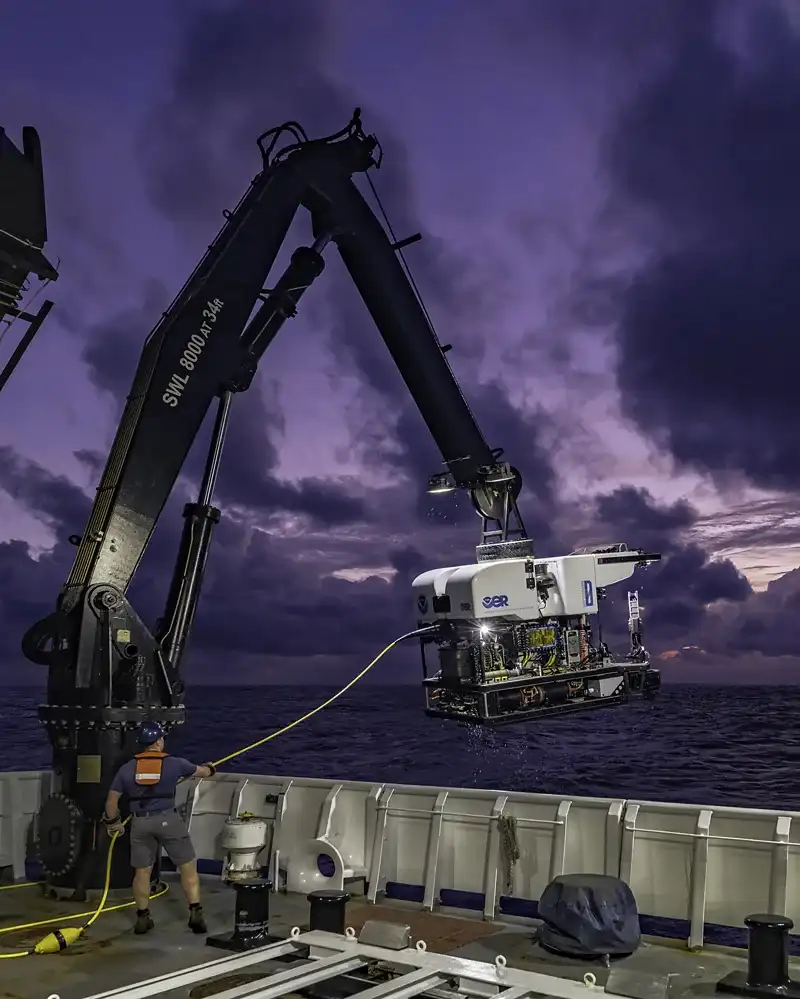

Trump’s executive order urges the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa) to streamline its permitting process. Yet critics note this conflicts with Noaa’s mandate to protect marine ecosystems. The agency responded by promising “science-based licensing and permitting” while also removing outdated regulatory hurdles.

Meanwhile, the international community is pressing for a moratorium. Over 900 scientists and policymakers have signed open letters demanding a halt to commercial deep-sea mining until further research is done. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos) governs international waters, but the US has never ratified the agreement — a gap that may further complicate oversight.

Balancing Innovation and Preservation

Some scientists believe that future technologies — including better sensors and computational modeling — may help mitigate the risks. Thomas Peacock of MIT, speaking at a congressional hearing, suggested that sediment plumes might be less impactful than feared. However, he acknowledged the need for off-limits conservation areas and further research to ensure safe practices.

What’s at Stake

As the debate heats up, the ghosts of past experiments linger. The tracks on the Blake Plateau remain a haunting visual reminder of just how long the ocean can take to heal. With commercial interest accelerating, Joye believes it’s time to pause and reflect:

“I see this place as a national treasure,” she says. “That mystery is something we need to solve, so we can serve as stewards of these habitats — not just exploiters.”

For now, the deep ocean continues to hold secrets that may never be recovered if its silent ecosystems are disturbed before we truly understand them.